Papua New Guinea History

The four pioneer RNDM’s who set out for the Southern Highlands of Papua New Guinea in 1969 were Sisters Mary Bernadette (Marion McLoed), Marie Lawlor, Mary Majella (Valerie Hogan) and Margaret Dorizzi.

The then Bishop Firmin Schmidt OFM Cap in his invitation to the Australian Province described in detail the aims of the missionary work in the Southern Highlands:

Our mission is in the location of one of the most primitive areas of PNG. The Southern Highlands was established only towards the end of 1950s. It would be a tremendous boost to our missionary work if you join us and staff Ialibu and Pangia along with the Capuchins and lay missionaries”.

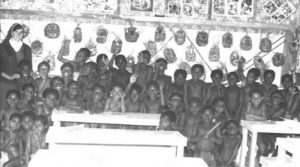

During the intervening years from 1969 until the last sister left in 2011 the Sisters adapted their lifestyle and apostolate to the changing needs of the local people. Initially the Sisters taught in schools but by 1972 Margaret Dorizzi had moved into pastoral outreach and the training of local catechists. Two Sisters initiated a vocational school. Eighteen Sisters in all were assigned at various times to fulfil specific needs. In Wiliame two nursing sisters Sisters Cherry Leonard and Roseanne Hammel staffed the clinic and patrolled into the villages to attend to the pregnant women and the sick and immunise the children.

In 1983 two sisters (Sr. Susan Smith and Marie Lawlor) staffed the Xavier Institute of Missiology in Pt. Moresby and later Sr. Rose Mary Harbinson joined the staff of the major seminary.

In 1986 Srs Maureen Belleville, Rose Mullan and later, Rose Mary Harbinson and Imelda Lyndsey went to teach with the Capuchins at St Fidelis College in Madang. Other involvements of the Sisters were at Tari High School (Sr Lois Hannan and Sr Carmel Looby) in the Hela Province and Sr. Susan Smith went to the Pastoral Center in the Inga Province. Sister Marie Lawlor the longest serving RNDM sister in her later years accompanied the Diocesan Congregation of the Franciscan Sisters of Mary in Kagua.

In August 1996 Maureen Dwan accepted the invitation to co-direct along with Sr. Lukas Suess, the newly established Diocesan Pastoral Centre. The residential centre offered short and long-term courses in leadership training to a wide spectrum of people including doctors, nurses, catechist, teachers, and catechists. Writing and illustrating various publications in Melanesian pidgin were an important part of the Centre’s life. These publications were geared to help the catechists in their ministry.

Some of the RNDM Sisters from Australia, New Zealand, England, Ireland and Canada who over the years spanning 1969–2011 served in the Ialibu, Pangia, Kagua, Tari and Mendi in the Southern Highlands, also in Madang and Pt Moresby.

My Story by Sister Maureen Dwan

I am a New Zealander, born in Rakaia, near Christchurch. I grew up in Christchurch and was educated by the Sisters of Our Lady of the Missions both in primary and at Sacred Heart Girls’ College for my secondary Education. In my late teens I joined the Congregation and after teacher training, I taught in Lower Hutt, Wellington and Christchurch.

To New Guinea in 1974

At an early age I had a great desire to go to Papua New Guinea, I realised this dream by joining the Australian Province. I arrived in the Mendi Diocese of the Southern Highlands in January 1974 and during my first year I became the head teacher at St. Clare’s Primary School and taught alongside Joan Forscutt and Pam Reynold.

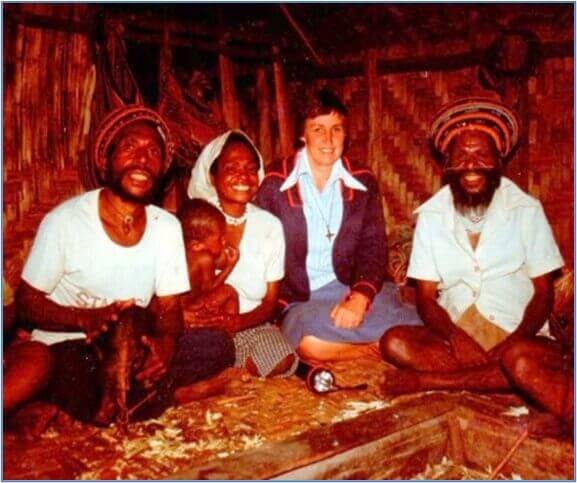

Although I had tenure, I opted to leave the classroom and began pastoral ministry in the remote area of Wiliame in the Last Wiru district. There I lived with lay missionary nurses from Australia who ran a clinic, I would accompany them on patrol, they, checking on pregnant women and immunizing babies while I worked with the catechists and helped them prepare the villagers for the sacraments. It would take us a week to visit half the circuit, staying with the villagers overnight. At the halfway point we would rest up at the Pangia convent and then complete the rest of the circuit.

One of the villages I visited called Tangupani, was deep into the bush and took eight hours to walk there. The people were nomadic and had only set up a temporary village. I was the first European woman to go there and as soon as the sun set, I was barricaded into a makeshift hut for my protection from the Sanguma (an evil spirit who killed), being hidden the Sanguma was not to know that I was there! A woman was with me and only at sunrise were we allowed out. Many nights the rain came, and the hut leaked! In all I made seven trips to Tangupani and each time notched a tree on the way to keep count.

The diocesan policy was that all those who wished to be baptised had to participate in the ‘Right of Christian Initiation’ (RCIA) programme. This often took a year or more. Polygamy was a common practice so this posed a big problem for male adherents to be accepted for baptism. All stages of the RCIA were played out in a cultural way, one such cultural enactment at a village called Kareni was filmed over a period of a year and is now in the archives of the Catholic Theological Union in Chicago as part of my Master’s in Theology thesis. All 200 men, women and children from three villages were baptised in the river…total immersion!

Ialibu in the 1980’s

In the 1980’s I moved with Margaret Dorizzi to Ialibu, a very big parish with 72 outstations to be served. Three Capuchin priests worked in the area. There were three distinct language groups, Kewabi, Imbongu and Wiru, with no language similarities. In the past the people feared moving about and tended to stay in their own valleys or on hilltops, and therefore developed their own languages. I communicated in Melanesian Pidgin and used an interpreter. I spent my time working between all three groups and had a great admiration and love of the people who were most welcoming and protective. During that time, a mentally ill woman arrived on our doorstep, she was a mother of seven children and with each pregnancy her mental state worsened. Initially we had no idea who she was or where she had come from. We cared for her as best we could, and she stayed for 5 years until a doctor tried out a magical drug called Modecate which gave her back her life. It was wonderful to witness her recall come to life.

Wonderful Cultural Experiences

I experienced many wonderful cultural customs. In my first weeks in PNG, I attended a pig kill where 1700 pigs were killed over three day between three villages. This cultural event only happened every seven or more years and is shown as a prestigious event and a way of compensating and cementing relationships with villagers from miles around. It was an extraordinary ceremony and still takes place today albeit on a smaller scale.

SingSings were another show of strength and power and a sight to behold when thousands of elaborately dresses warriors would dance for days sporting their beautiful headdress of Bird of Paradise feathers.

The lifestyle of the people of the Southern Highland was very simple and as a European I would say primitive. When I first went to PNG the people still wore traditional dress, a grass skirt for the women and a bark belt and bilim for the men. Most of the children were naked until they were 9 or 10. Their thatched homes were one room with a fire in the centre where the people cooked, sat, told stories, and slept, often the pigs, dog and chickens were also in the house. The food was simple, sweet potato and greens and occasionally some tinned fish. Over the years the diet improved for many, rice was introduced and if the people were financially able a little meat. They also hunted for birds and mammals.

When I first arrived the only way into the Southern Highlands was by plane and the mission had a small plane which dropped food goods, fuel and building materials into individual mission stations. While this was happening the roads and bridges were built. Because of the daily heavy rain, the roads became very difficult to navigate and we often became bogged. Access to villages often involved hours of walking up mountains and fording rivers.

I had many wonderful encounters with a great number of highlanders, one that was extraordinary and is worth writing about is the day I met Wata. I was called to the Riwi village and there I met a little man barely five feet tall, covered in mud, matted hair, and wearing a few leaves. He had very limited language skills, however through an interpreter he told me his story. He lived in a very remote part of the forest and very few people ever passed his hut. His mother died when he was a baby and his father raised him. On his father’s death bed when Wata was just 11 years old his father made him promise that he would guard their land from tribal enemies. Wata buried his father and from then on lived a lonely life, he told me he talked to the birds and the animals. When he was about twenty years old, he went further afield and came to the village of Riwi. There he watched a catechist preparing a group of people for baptism. He sat on the periphery of the village and heard something about Jesus, Mary and baptism. He then trekked back home. After that he told me he began talking to Jesus and Mary and they talked to him!

It was hard to know at what age Wata was when I met him, possibly 50 years or older? He told me he was going to die and that he wanted to be baptised. How did he understand the significance of Baptism?

As mentioned above, the diocese had a policy that the RCIA programme was to be followed in preparation for baptism. I did not think that Wata was dying but I realised that there was no way he could be part of an RCIA programme and that if he was conversing with Jesus and Mary then what more did he need to know? I was able to convince the Capuchin priest that I worked with that he should come and baptise Wata. The following day the people erected an altar under a tree, they took Wata and washed and oiled his body and gave him a bark belt and head bilum. I gave him his baptismal candle and a large pair of fluorescent rosary beads! Wata was baptised, received his first Holy Communion, and was Confirmed in a wonderful liturgical ceremony followed by a feast prepared by the villagers. Later in the evening Wata went from hut to hut and thanked the people and returned whatever had been given to him. He then said he was tired and was going to sleep. A few hours later Wata’s body was found in the garden of one of the villagers, in death he was still holding his candle and had the rosary beads around his neck. I was shocked to hear of Wata’s passing and wondered why I had not been called to be part of his burial which took place the next day. When I queried this the response of the church leader was “Didn’t he tell you when you met him that he was going to die!”

I could relate countless incredible encounters and experiences, and maybe one day I will write my story. I would just like to conclude by saying that my 29 years in Papua New Guinea were a wonderful and enriching part of my life. There was a wonderful relationship between the Bishop, priests, sisters, and lay missionaries. I met and made friendships with thousands of Papua New Guinea nationals, many of these relationships have endured to this day. There were times when there were difficulties between tribes, and tribal fighting would break out and lives lost. Often, we were able to intervene and help cement relationships. I felt very blessed to be in Papua New Guinea in the early years of development of the diocese, an experience of a lifetime that I thank God for.

Rome, England and Melbourne

I left PNG in 2002 and took up an assignment on our leadership team in Rome. In 2009 I was asked by the England/Ireland Province to set up a heritage centre in Sturry, England (outside of Canterbury) in memory of our foundress Euphrasie Barbier, this took me two years. I had planned to return to New Zealand in 2011 but was invited by the Australian Province to work with Sr Catherine Brabender in the International Mission Development Office in Melbourne and this is where I am today. New Zealand is still in my sight.